Being primarily an Economist, and the newest member of the group, I still have a lot to learn about the demographic changes affecting Virginia and the US. So attending the Applied Demography Conference 2014 was a very educative experience for me. One of the subjects I found particularly interesting was school level projections, so here are some thoughts on the subject.

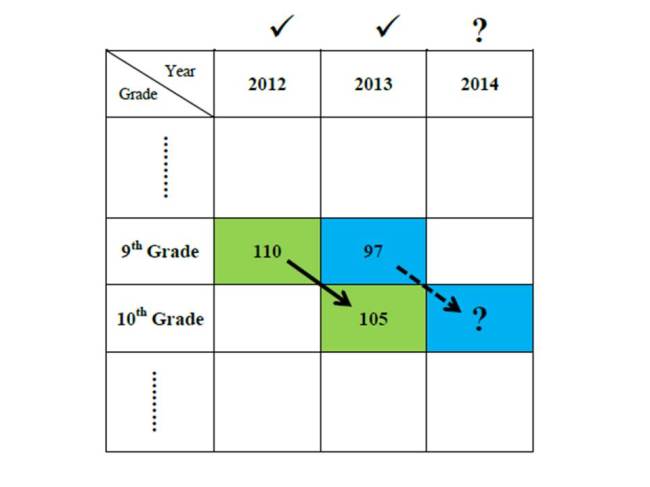

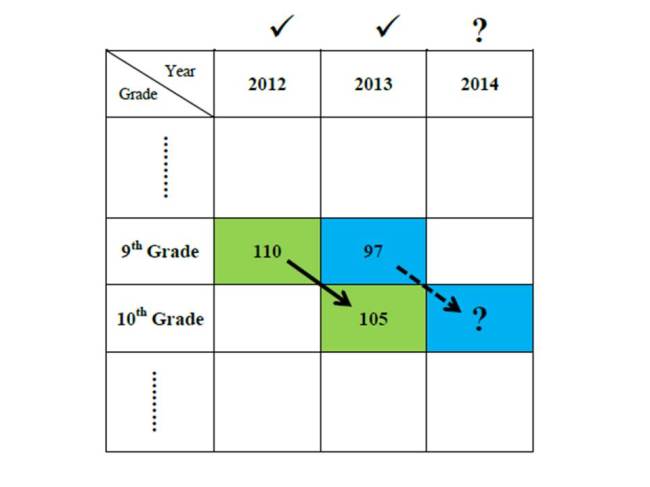

School enrollment projections are crucial for staffing, budgeting and classroom allocations as school districts rely on these numbers to anticipate future needs and plan accordingly. It is reasonable to assume that number of students in a particular grade will depend upon the class-size of this cohort when they were in the immediately preceding grade. Consider a batch of students moving from 9th to 10th grade between 2012 and 2013.

If everything remained constant, all 110 9th graders from 2012 should progress to 10th grade in 2013 and so forth. However the numbers are not always the same which could be due to several reasons. As we go from 9th to 10th grade, 5 more students could have joined the cohort in 2013 so the class-size would grow to 115 as some new children may have moved into the school district from elsewhere. Alternatively in 2013 when we follow these 9th graders into 10th grade there may be 5 fewer students, making the class size 105 for the next year. Some of these children could have remained in the previous grade to repeat a year, they may have left to join a different school or may have dropped out of school altogether causing the class-size to shrink. Hence all students from a grade may not automatically advance to the next higher grade and we need a method for estimating future class-sizes. Grade Progression Ratio (GPR) is the standard go-to for forecasting school enrollment. To see how this works, suppose you are a school administrator who needs to know how many students to expect in the 10th grade in 2014.

From the example above we find that GPR9th-10th = 10th grade Enrollment in 2013/9th grade Enrollment in 2012 = 105/110 = 0.95, which implies that we expect 95% of students in 9th grade to move on to 10th grade. To calculate the current enrollment for grade 10 in 2014, we can apply the progression rate from last year: 10th grade Enrollment in 2014 = 0.95 * 97 = 92.59. Therefore approximately 93 students are projected for the upcoming year. This is a simplified illustration of how we may predict the expected number of students in different grades in the future. In practice, we use data from multiple years to build ratios in order to minimize randomness and several other elements must be incorporated into the calculations to get greater reliability.

Here are some other updates and advances about enrollment projections:

- One way to calculate future student enrollment in rapidly expanding areas is to track new residential developments (historical trends, current construction, home sales etc. are indicators of single-family and multi-family presence in the school districts) for creating different area-specific yield factors.

- For each new house that is constructed, there are several pre-existing homes that exchange hands; so neighborhoods could evolve even though number of housing units remains steady. New families come into ownership of these resold properties changing the population composition which in turn may change the demand for schooling.

- Migration alters the prevailing age structure and family type of a locality which will determine schooling needs. Number of school age children in a household fluctuates over time and migrating households could contain elderly individuals with adult offspring or they may be young families planning for or already with children. For example, a 3rd grader moves with the whole household while a college student moves alone and movement of empty-nesters will not add new students to an area.

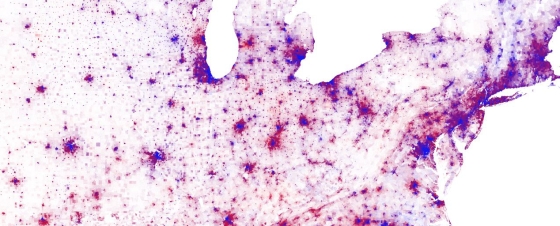

- Geo-spatial analysis has become an indispensable tool for understanding modern demography. Families move and household composition changes, therefore the geographic distribution is useful for identifying trends in student yield with variation in housing tenure. Plotting child-densities on a map helps to visualize concentration of students in a school district and could improve the accuracy of projections.

- Public school enrollment rates may be affected by presence of private schools among others; the odds of attending a private school significantly depend upon household income, race and neighborhood of residence. The economic climate also plays a significant role as in times of prosperity more families can afford to send their children to private institutions. Public schools will receive more funding during economic booms as opposed to times of recession when the financial downturn percolates into both household and administrative schooling decisions.

All trend projections and estimates are speculative in nature which means that there is a constant need for dynamically updating the statistics. Here at the Weldon Cooper Center, every year we conduct school enrollment projections under contract with individual school divisions. We apply Grade Progression Rates for general analyses and implicitly take account of net effect from migration, dropout, deaths, retention, and school transfers. For more customized analyses, we include further nuances into the methodological design such as housing development, family structure, differential fertility rates by race and ethnicity etc. to incorporate location specific characteristics. For more details please visit our School Enrollment Projections page.

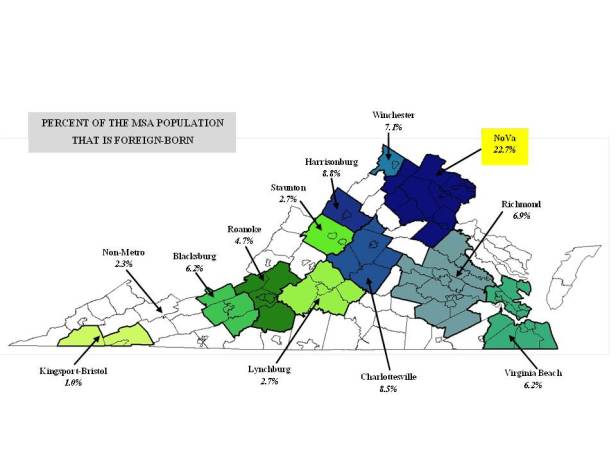

The distribution of foreign-born people among Virginia’s 11 metropolitan areas (MSAs) can be seen in the map above. Close to 70% of immigrants can be found in Northern Virginia alone, with Hampton Roads and Richmond hosting about 10% each. Among the smaller MSAs, Charlottesville leads the pack with nearly 20,000 foreign-born individuals, many of whom are students, faculty or staff at the University of Virginia. The non-metro, mostly rural areas are home to less than 3 percent of the foreign-born.

The distribution of foreign-born people among Virginia’s 11 metropolitan areas (MSAs) can be seen in the map above. Close to 70% of immigrants can be found in Northern Virginia alone, with Hampton Roads and Richmond hosting about 10% each. Among the smaller MSAs, Charlottesville leads the pack with nearly 20,000 foreign-born individuals, many of whom are students, faculty or staff at the University of Virginia. The non-metro, mostly rural areas are home to less than 3 percent of the foreign-born.